What did you do for one of these brothers of Mine, even the least of them? Matthew 25:40

The story behind the paintings

April 15 1945 Bergum | 90 x 110 cm | 2024| oil on canvas

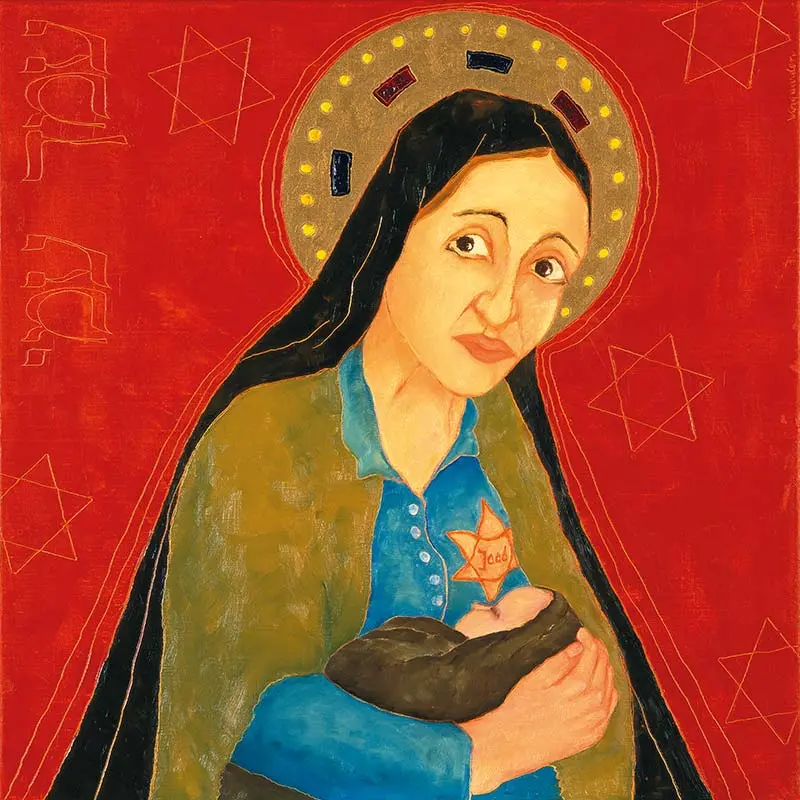

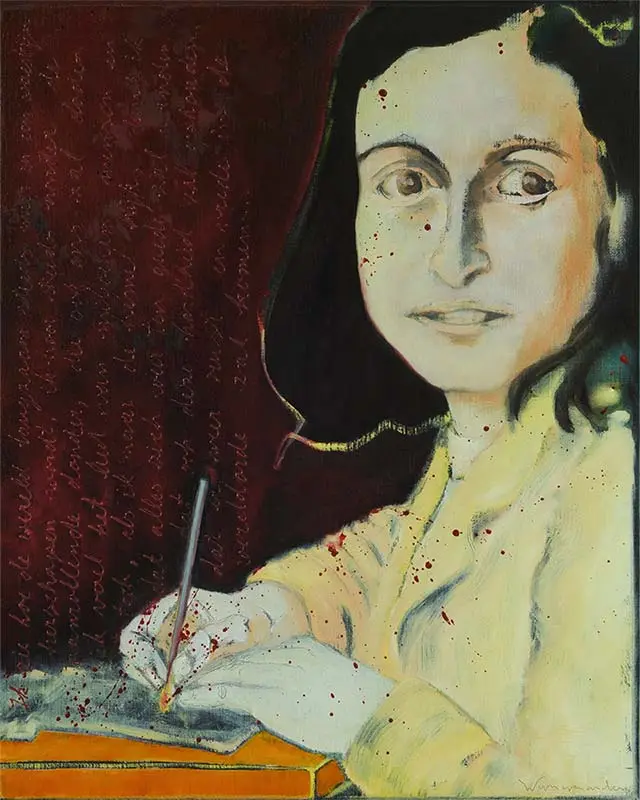

When I was approached about the opportunity of an exhibition in the Jacobijnerkerk in Leeuwarden, opening on 15th April 2025 to commemorate the 80th anniversary of Liberation, my mother gave me her poetry album from 1944-1945, with rhymes written by her young friends who were in hiding. She also gave me photos of the very pious family Douma who had taken her in, as well as many of her handwritten letters.

My mother, Ankie Besnard-Walch was taken from Amsterdam by child transport during the Hunger Winter of 1944. It was a dangerous undertaking, crossing the Afsluitdijk in order to house the emaciated children with families in Friesland. Ankie was sent to Bergum, a village close to Leeuwarden. It was there that she witnessed the Liberation on 15th April and wrote to her mother: “Hurrah hurrah, we have been freed. Oh mother, I’m so joyful that we’ve been freed. We were liberated on Sunday morning (15th April) and everything went well. There was no fighting here at all.”

My mother died in the summer of 2024 at the age of 93. This painting is my farewell to her. The cockerel, the symbol of France that I embroidered at my grandmother’s place, is my final salute to her.

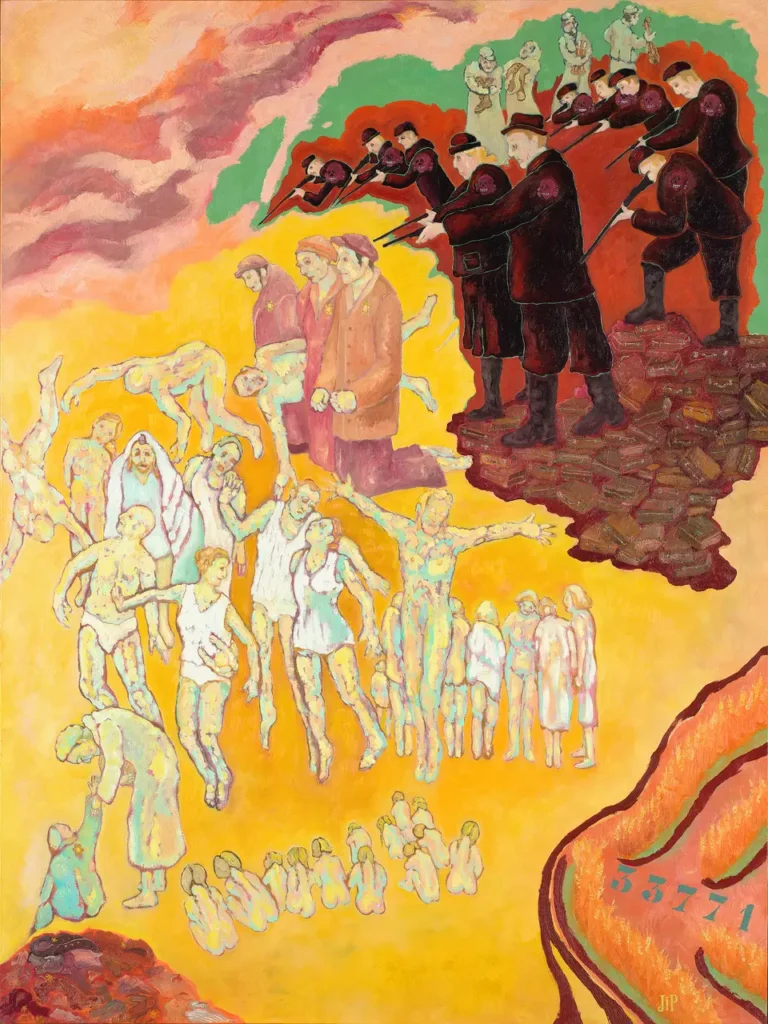

Babi Yar | 160 x 120 cm 2x | 2024 | oil on canvas

The diptych depicts Jews from Kyiv being executed by the German Einsatzgruppen while people walk away laughing, carrying the personal belongings they have stolen from their Jewish neighbours.

Just outside Kyiv, at a place called Babi Yar, 33,771 Jews were slaughtered and shot in just two days on 29 and 30 September 1941. The tragedy took place on the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, Yom Kippur.

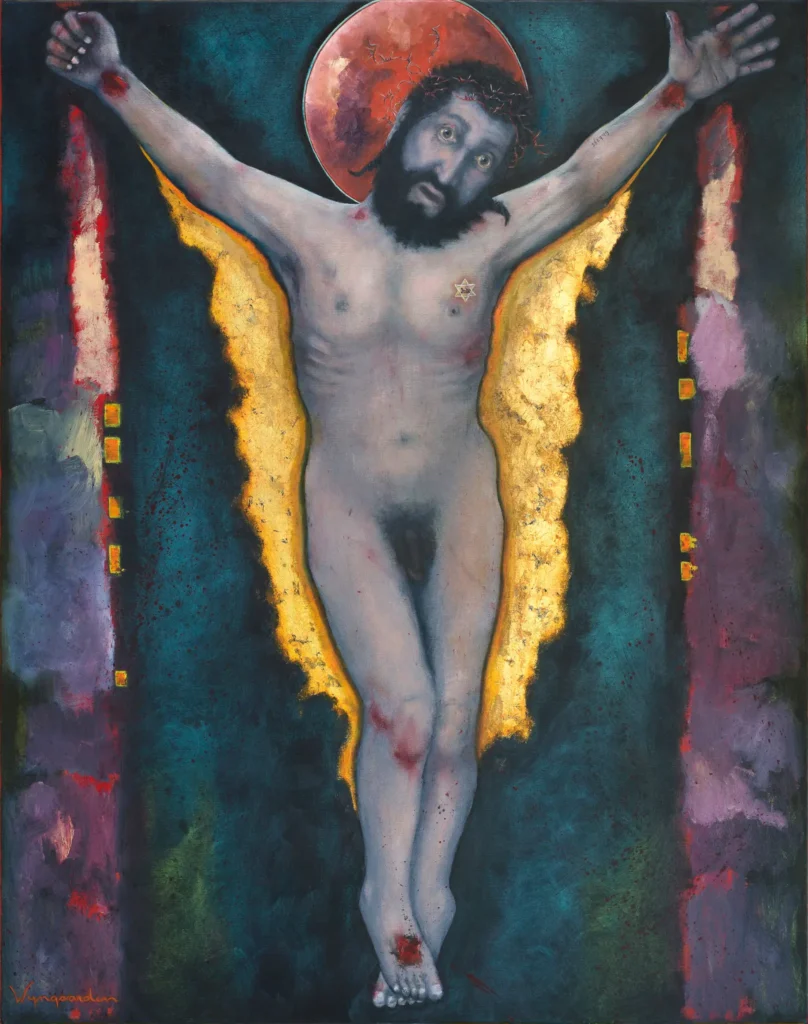

On the right half of this diptych, we see Jews who were humiliated and murdered during the Second World War. However, on the left half, they rise from the dead.

Psalm 147 states: He counts the number of the stars; He calls them all by their names.

The Eternal One counts the Stars of David and calls them by name. He will write them in the Book of Life, while the Einsatzgruppen disappear underground like skulls and crossed bones.

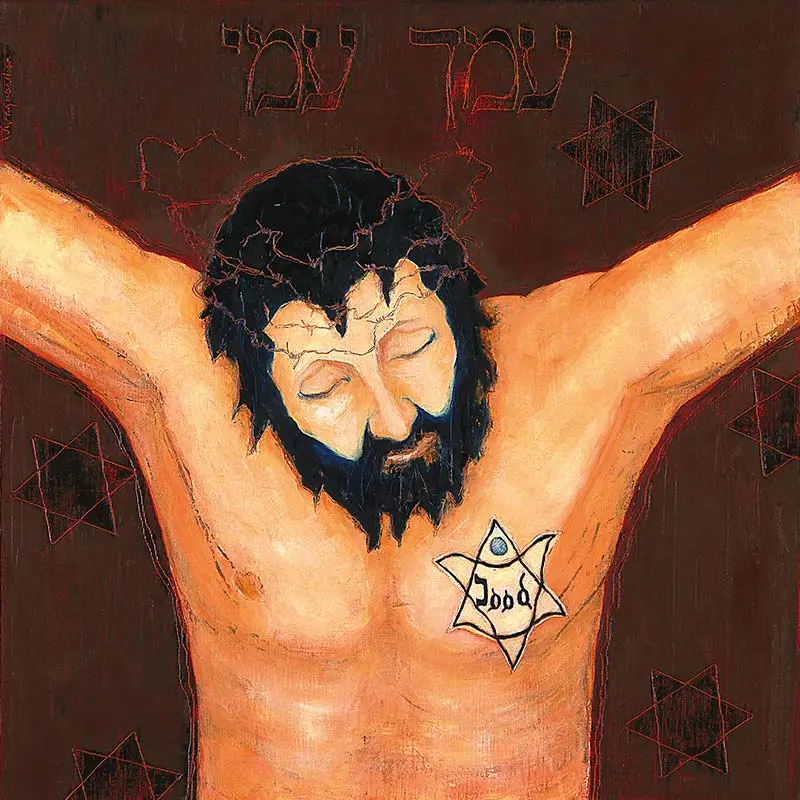

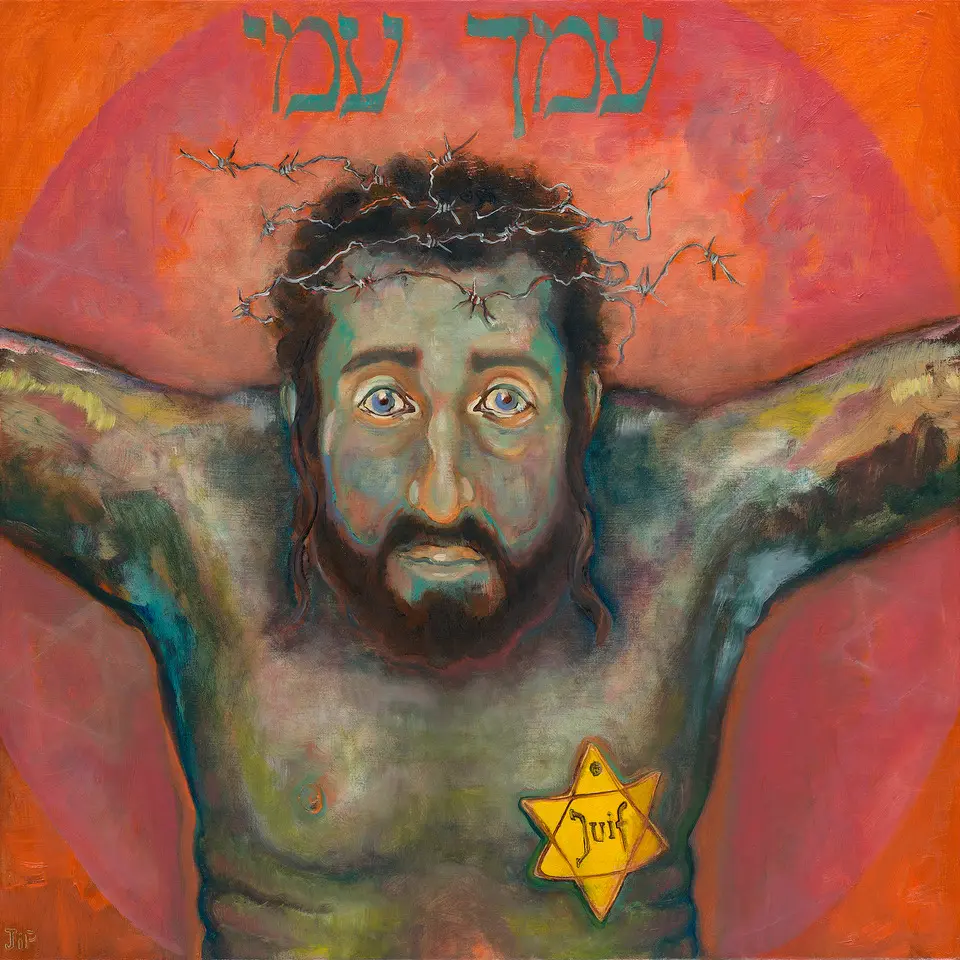

Jesus also belongs to those executed. If He had lived in Kyiv in 1941, He would not have sat safely in a church on a beautiful wooden pew, but He would have been dragged away and executed along with His own Jewish people, by those who called themselves Christians but did not live in the truth of that set of beliefs.

The painting bears a subtitle from Matthew 25:40: Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers of Mine, you did for Me.

Sjofar

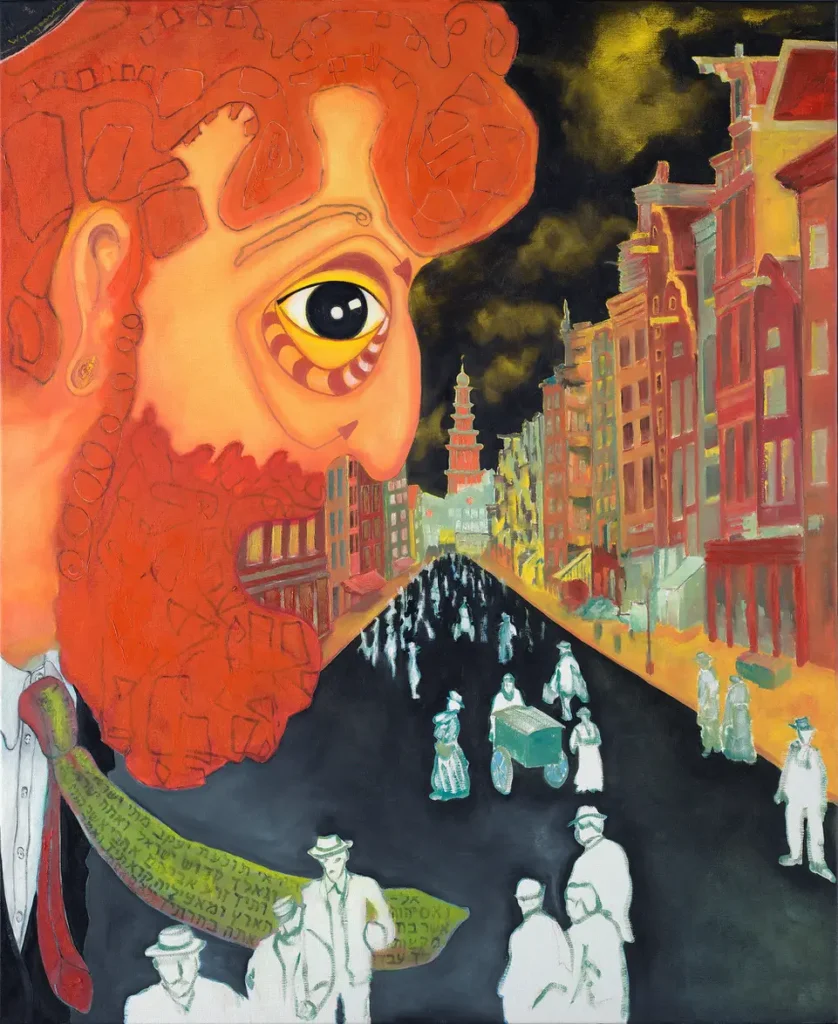

Shofar| 160 x 120 cm | 2005 | oil on canvas

A prophet, a seer, flies through the scene, blowing the shofar, the ram’s horn. A small village without windows, a railway track, and Jewish people gathering. They wait for deportation. Suitcases. Desperate faces. Two elderly people looking at each other:

“Did we remember to turn off the lights?” A young, pregnant woman has left her home barefoot. Her little daughter tugs at her skirt. She does not notice. Everyone is lost in their own personal tragedy. What they do share is the fear of what is to come. One man lifts his head and looks towards the church tower, towards the cross—the sign of the suffering Messiah. But the church shutters are closed.

This painting about the Shoah is inspired by Proverbs 24:11-12: Rescue those being led away to death; hold back those staggering toward slaughter. If you say, “But we knew nothing about this,” does not he who weighs the heart perceive it? Does not he who guards your life know it? Will he not repay everyone according to what they have done?

The echo of a recent past: “Wir haben das nicht gewusst” (We did not know) – is a condemnation of ourselves.